Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) are three factors commonly used by socially responsible investors to measure sustainability and ethical impact of an investment in a business or company. Recently, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) published a proposal with amendments and rules regarding disclosure of ESG reporting and data intended to ensure that investors receive information related to ESG that is truthful, comparable, and dependable across funds and advisers.

Because ethical technology can be subsumed under the “social” category and indeed, may well emerge as its own ground for consideration of sustainability by investors, the SEC’s proposal can be seen as a harbinger of things to come for AI ethics as well. And to the extent the faith world comes to understand and distinguish ethical AI-powered applications from destructive technologies, faith-based investment capital is likely to follow.

SEC Chair Gary Gensler stated that these disclosure requirements will allow investors “to see what’s under the hood” of the ESG strategies so they can make informed decisions “to allocate their capital efficiently and meet their needs.” The SEC proposal is part of a set of actions taken by the SEC to protect investors, such as the creation of the SEC’s Climate and ESG Task Force in the Division of Enforcement growing out of a series of enforcement actions against mutual fund advisers and funds alleged to have mislead investors on ESG reporting. The proposal shows the significant risk that misleading and false ESG reporting poses not only for investors but for society at large.

It is in this financial environment characterized by a lack of valid measurements, standards, and coherence that faith-based investment must evolve. Currently so-called “impact investing” resembles a tohu-bohu situation where there are no rules because there are no rulers, and there are no rulers because there are too many rulers. Let me develop this.

Impact Investing (including Faith-based Investing) Needs a New Paradigm

Impact investing is a field with multiple stakeholders whose interests are not necessarily aligned, and yet, they desire to work together to address today’s environmental and social problems. These stakeholders — governments, civil society, businesses, and markets — find themselves ranged around a table of sustainability, with table stakes being the flourishing future of humanity. Each of these stakeholders oversees specific areas of society with specific objectives and standards. Hence, the need for synchronization of strategies and actions towards a unique goal: building a sustainable world.

The high stakes around this table of sustainability suggest the need for a new structure, where the public sector and the private sector can join hands with a third sector – the faith world – to combine their influence and power to create favorable conditions for a more sustainable society. At the intersection of these three sectors we may find a solution to the key questions of who is regulating what, when and how? Indeed, this third sector might be destined to lead the path forward as it already has long experience in managing competing values and addressing social and environmental issues.

Our challenge is to align these ESG objectives synergistically towards a single outcome, a sustainable world. Think of a concert where various musical instruments together play a symphony. Each instrument has its own contribution, yet they play in concert to produce a unique, complex, and harmonious sound.

Nowadays, impact investing is far from presenting a harmonious sound. For example, recent research on ESG ratings shows that instead of bringing more clarity and precision, today’s ESG disclosures lead to significant disagreements in metrics. The main consequence of such disagreements is “higher return volatility, larger absolute price movements, and a lower likelihood of issuing external financing.” These findings are consistent across studies, to mention only a couple of them published in the last months.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), unfortunately, do not offer a better alternative to ESGs. Recent research evidence deep inefficiency of SDGs. Over the years, SDGs have not produced a transformative impact. Rather, their limited contribution is mainly to provide better terminology for understanding sustainable development, but even as to this there is much disagreement. In other words, SDGs are in the same situation as the ESGs.

The field of impact investing is still looking for a workable paradigm that meets the complex challenges of ESG in an efficient way. However, progress is being made incrementally. What is needed are new paradigms and definitions that offer an integrated approach, going beyond the ESG or SDG frameworks, both suffering of a clustered approach of issues. Indeed, actual practices are tackling separately the E, the S, and the G in ESG, with an almost exclusive attention on the Environmental for practicality reasons mainly having to do with ease of impact measurement. SDGs likewise suffer from the practice of choosing to focus on specific SDGs among the seventeen proposed by UN, while in reality they are linked, interdependent and systemic.

Such a new paradigm would need to consider the fuzziness of this epoque caused by technological and cultural value shocks, which in turn contribute to the fuzziness in impact investing. In the end, we must recognize that the investment outcomes we seek to achieve are dependent on people: how they act and react to the changes that impact investing seeks to bring about. This is obvious from a careful reading of classical economic theories from Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill stretching to recent work in behavioral economics (for discussion, see Acatrinei, 2008). The key problem lies in working assumptions in economics and finance that rely on the rationality paradigm, whereas most of the time, people make decisions in more of a system1 process– intuitive, instinctive, rather than a system 2 process– deliberative and logical.

A key question is whether the faith sector might in fact better understand and take into account this fuzzy environment, and promote a better synchronization with the public and private sectors? Are faith actors in a better position than the other actors to understand how to invest in products and programs that motivate people to achieve desired outcomes, and thus achieve the “philharmonic of impact investing”? I will make a case here that faith-based investment shares the inherent characteristics of this fuzzy environment for ESGs (including ethical technology) regarding risks and opportunities and has also has its own peculiarities and advantages.

Challenges and risks of faith-based impact investing

There are two groups of challenges and risks faced by faith-based impact investment:

The first group of challenges arises out of impact investing in general. These are:

1. A lack of harmonization between many categories and measures under the umbrella of ESGs and SDGs, a lack of standardized definitions, and a lack of valid and reliable metrics and consistent rules are ubiquitous.

2. The failure of ESGs and SDGs and other related factors to generate trust may be the most important phenomenon preventing the development of a sustainable society.

3. “ESG-washing mania” which in the faith realm takes the form of faith-washing is the greatest challenge of impact investing, and such “washing” often is no less a problem where the key investing factor is “faith.” However, I argue that faiths should have a comparative advantage vis-à-vis secular impact investing for the reasons I discuss below.

The second group of challenges is related to the diversity of faiths and the way they practice impact investment, leading to:

1. unequal development of impact investing opportunities and strategies across faiths/religions

2. a lack of standards within and between faiths/religions

3. a lack of coordination between faiths/religions and the secular impact investing

Opportunities and advantages of faith-based impact investment

While faith-based impact investment shares some of the same challenges and risks as the secular impact investment, it also has, significant comparative advantages, mainly in defining standards:

- Faiths already have a methodology that allows them to establish clear and consistent standards across investments based on doctrines and teachings which are known and accepted by the faith stakeholders. In other words, faith investors, as long as they secure an alignment between doctrines and investment, benefit from an intrinsic validity, so to speak, of these standards based on their sacred texts.

- For example, just recently, on July 19th, the Vatican announced a new investment policy aligned with Catholic teachings and doctrines, and the creation of a unique fund that will be channeled to various financial instruments. The stated goal of this policy is to help create a more just and sustainable world. Father Juan Antonio Guerrero, the Prefect of the Secretary of Economy, distributed this new investment policy to relevant actors within the Vatican, such as the chiefs of various dicasteries/departments of Curie, and to leaders of various other institutions and organisms within the Holy See.

- Moreover, faiths have the possibility to enforce a double impact when promoting impact investing: first, through religious institutions’ funds such as the Vatican unique fund; and second, through individuals who want to invest their personal fortunes according to their faith values (e.g., pro-life, pro-natura, against weapons, etc.)

- Faiths have been engaged in philanthropic activities for centuries. Indeed, the faith sector for impact investing is nothing less than the outcome and development of traditional religious institutions that continued their work and engagement in society as the state little by little took a larger place in nation-state formation and development. Organizations active with the highly diversified and complex faith sector still share their DNA with their religious based ancestors, providing services and products that benefit the public out of love for humankind and without looking for retribution. Indeed, it is does not go too far to say that this sector originated impact investing, through negative screening implemented by religious institutions that refused to invest in harmful industries.

- Faiths also pioneered positive screening, meaning investing in activities that have a positive impact on society, such as education, healthcare, environment, etc. Through such positive screening, faith-based impact investing not only avoids investment in harmful industries (e.g. negative screening) but has a pro-active role in choosing to invest in those activities with a positive impact on society. Faiths didn’t wait for the SDGs or ESGs to engage in social and environmental impact. Rather, I would contend that SDGs and ESGs “owe” to faiths their own existence, hence, a rich experience that faiths could share with stakeholders when it comes to social and governance impact.

These are some of the considerable advantages which allow faith investors to step forward, and maybe even to lead the movement of sustainable finance. However promoters of faith investing also need to continue to change and adapt in the face of the same challenges faced by public and private investors.

Improving Faith-Based Impact Investing.

Promoters of faith-based investing need to create a new Financial/Investment vocabulary addressing both the religious identity and needs of religion-centered actors. Essential to this is identifying intersection points between faith-based activities and financial strategies such as negative and positive screening, blended finance, impact investing, social impact, sustainable investment, integrated investment, etc.

Both secular finance and religion are still innovating and searching for optimal solutions. Hence, there is a need to coordinate efforts of faith-Invest actors with secular financial markets through a reciprocal learning process of concepts and processes to co-create new financial instruments.

Finally, both secular and faith-based impact investment promoters need to ask, “what is the right benchmark?” Financial benchmarks in faith-based investment are shifting from negative screening (eliminating investing in vices) to positive screening (practicing good stewardship and promoting virtues). Negative screening is easy to design and implement, while positive screening is more difficult, if not impossible, to construct a benchmark that will be accepted by all faiths. In other words, faiths are facing the same problem of accuracy, validity, and reliability of measurements that ESGs and SDGs already confront.

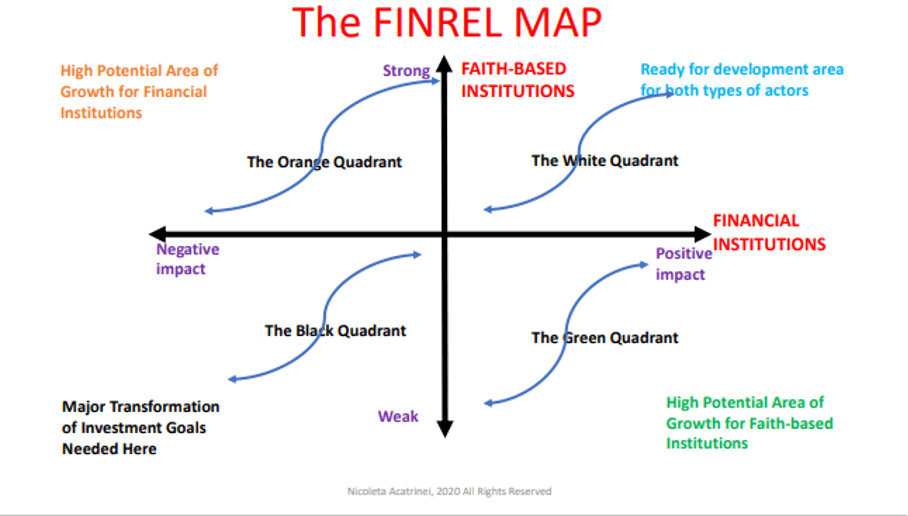

These challenges notwithstanding, faiths have some comparative advantages when it comes to interacting with financial institutions. To show the area of opportunities at the intersection of faith and finance, I have created this FINREL (Finance & Religion) map to highlight how religion can trigger financial behavior by enhancing the need for social and spiritual impact.

To understand the map, we need first to account for the heterogeneity of actors, of their motivations, and of the rules they follow. The FINREL map allows us to identify four situations depending on the strengths of religious institutions and the impact of financial institutions.

To map the interaction of faith and finance, I propose a model where faith-based institutions represent the vertical axis, with two poles, strong and weak faith institutions. The strength or the weakness refers to how articulate the faiths have been about their investment strategies and how consistently they have tried to align faith values with investment decisions (e.g. Catholic, Protestant, Islam)

The horizontal axis represents financial institutions and the impact of their investment strategies, a positive versus a negative impact (e.g. climate versus resource extraction, education versus weapons, etc.)

At the intersection of faith and financial actors, the model illuminates four situations of opportunities and challenges. For example, when faith-based institutions are strong and financial actors already privilege a positive impact, the opportunity for collaboration is already in place, hence, the conditions are optimal for faith-based impact investing. At the opposite quadrant, the black one, faith-based institutions are weak and do not develop any strategies for social and economic impact, while financial actors privilege investing in harmful industries. Thus, there is little opportunity for faith-based impact investing. However, as the orange quadrant shows, when faith-based institutions are strong there is a potential for them to collaborate with financial actors who have a negative impact, to change and innovate in faith-based impact investing. A similar situation exists in the green quadrant where financial actors are impact oriented and engaging with faith-based institutions to leverage their impact while strengthening the latter and helping them to align faith values with investment decisions.

Figure 1 Mapping Faith and Finance Opportunities (Acatrinei, 2019)

The FinRel Model suggests these Implications and challenges:

a) Depending on the strength of Faith-based institutions as well as on the positive/negative impact of financial institutions – each actor has an optimal area of development.

b) The development areas show the challenges faced by these actors and their respective optimal strategies.

c) This is a dynamic model – actors can move from one quarter to another.

d) New variables are to be considered along with return and risk, such as social and spiritual impact.

In sum, the FinRel model suggests there is a need for new integrated theoretical frameworks at the cross-roads of theology/religious studies and finance – hence, the need for alignment of ESG, SDG approaches with faith-based concepts.

Conclusions:

- Faith-based Investment is a field still in need of more mature theoretical and practical perspectives.

- Faith-based actors should take the lead with civil society on specific topics, where faith has long term experience, to reshape financial and economic powers.

- There is a need for faith-based actors to rethink their role in society, including their respective theologies, with the goal of creating new financial instruments.

- A lexicon is needed for faith-based impact investing recognized by both religious and financial institutions.

- The faith sector might offer a platform where the public and private sectors come together to design joint solutions for sustainable development.

In sum, I contend that faith-based institutions need to practice a two-way strategy, externally and internally oriented, in order to create a real transformation in impact investing. Externally, faith-based institutions need to propose products and services which respond to non-faith-based institutions and individuals, so they do not become isolated from the broader investment community. Internally, they need to innovate in the area of philanthropic activities applying sophisticated investment principles to create greater impact by the faith-based sector and also to attract new financing sources, including non-faith-based sources. It is important for faiths and financial actors practicing faith-based impact investing to collaborate with sustainable development actors and stakeholders, and thereby promote innovation in theological foundations of impact investing. As shown in the FINREL map for growth opportunities, this could lead to the creation of new financial instruments that will benefit the entirety of the market and humanity.

Finally, a crucial role in this field is played by personal faith motivations of financial players when their decision-making is guided by religious beliefs and mainly by a personal and intimate relationship with God. I think of actors such as Cathy Wood from ARK Invest or Robin John from Eventide, to mention only those I have personally met. Their faith is at the heart of their decision-making in an implicit or explicit way. Investing in the future and in innovation means enhancing the creative power humans are invested with (Cathy Wood), Investing in human flourishing means to invest in God’s plan for humans as described in Biblical writings (Robin John).

—

Proposing Release: Enhanced Disclosures by Certain Investment Advisers and Investment Companies about Environmental, Social, and Governance Investment Practices (sec.gov)

For a more detailed analysis of this topic, read the paper “When the Third Sector Becomes the First Sector, Again!,” Nicoleta Acatrinei, Ph.D., 2020.

Christensen, D.A. at all. 2022, “Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder”, in The Accounting Review 97 (1), 147-175.

Alkaaran, F. et all. 2022, “Corporate transformation toward Industry 4.0 and financial performance: The influence of environmental, social and governance (ESG), in Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175, 121423; Serafeim, G. and Yoon A, 2022, “Stock price reactions to ESG news: The role of ESG ratings and disagreement”, in Review of accounting studies, 1-31.

Scientific evidence on the political impact of the Sustainable Development Goals | Nature Sustainability

Scanton Kyle, Opinion Today: The vibes are off-and that could impact the economy,” in The New York Times, 6 August 2022.

“Adam Smith wrote a Treatise on Moral Sentiments, which he regarded as his most important book, but was dethroned by another book, The Wealth of Nations, which was to make him the father of economics. Yet, the fate of the homo economicus was going to be influenced by the Ricardian perspective which no longer analyzes man as part of a social ecosystem, but only in a narrow framework of purely economic relations. Homo oeconomicus was born in the mid-nineteenth century and had as its father the utilitarian philosopher Bentham and as mother the Ricardian economy reinforced and developed by John Stuart Mill. The result is a purely hypothetical construction; its definition can be compared to the way in which a straight line is defined in geometry. Homo eooconomicus’ story began in a purely imaginary world, and classical economists are aware of its limitations.” p.9, Acatrinei, N. 2008, Saint Jean Chrysostome et Homo Oeconomuicus, USA,

Kahneman, D. 2011, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

New Vatican Policy Says Its Investments Must Align with Catholic Teaching – Catholic Daily

See Acatrinei 2008 about spiritual impact on financial decisions.

See Acatrinei 2021, “The Theological Foundations of Impact Investing”, book draft based on Acatrinei ASREC papers from 2018, 2019, 2020.

See more about this analysis in a working paper Acatrinei, 2022: “Faith and the opportunity cost of impact investing. Modelling fintech narratives from the religious vantage point of markets.”