The Ars moriendi—the art of dying—in every age, cultures have wrestled with it.

Romans staged funerals with civic spectacle, but in the catacombs beneath Rome I witnessed another vision: early Christians burying rich and poor alike, prayers carved into stone. No hierarchy. No spectacle. Just presence, hope, and the promise of resurrection.

Today, in an era of AI-powered analytics, algorithmic forecasts, and assisted dying legislation, we risk reducing death to a data point, a managed outcome, a scheduled exit. The Christian story interrupts this calculus with a paradox: the art of dying is not ours to perfect. It has already been perfected in Jesus Christ.

On the cross, Christ did not cling to life as possession. He gave it away — “No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord” (John 10:18). His dying is not a capitulation to despair but a radical gift so that others may live. In Him, death is not the end of liberty but the opening of eternity.

As a Christian, His art of dying gives me never-ending awe. My conversation with Him remains: “You gave your life to give me mine? Why?” In that question lies the mystery every algorithm misses. As a bioethicist, that same art of dying reframes our ethical debates about dying. If the ultimate art of dying is Christ’s self-giving, then the measure of our practices—whether in medicine, AI, or public policy—requires a deeper reflection. He gave it freely, not for efficiency or prediction, regardless of whether the one who received that gift would honor their life as gift or not. No conditions attached.

Oberammergau, 2022

In 1633, as plague swept Bavaria during the Thirty Years’ War, the villagers of Oberammergau vowed that if God spared them, they would perform a Passion play every ten years. The following year, they kept their vow, and nearly four centuries later the tradition endures.

In 2022—delayed two years by the Covid-19 pandemic—I sat in their open-air theatre, watching more than 2,000 villagers enact Christ’s final days: His entry into Jerusalem, His suffering, His death, and a subdued yet luminous Resurrection. It was not a spectacle of civic memorial but a community keeping vigil together, practicing the art of dying—not as arithmetic, not as prediction, but as gift.

For me, it was not just a play. It was an encounter that made me think again about why He died the way He did. The Oberammergau Passion Play reminded me that the true art of dying is not control, but surrender. Not calculation, but communion. Not prediction, but presence.

Prediction Is Never Destiny

In an age of genetic determinism and predictive analytics, we are tempted to believe that longevity can be scored, dying calculated, caring reduced to a timetable. But the art of dying resists such arithmetic.

Genetics, class, and habits shape lifespan, but only modestly. Twin studies, genealogical analyses, and centenarian studies all converge on the same truth: prediction only explains a little. Even the most advanced AI cannot account for contingencies —accident, infection, resilience, the sheer surprises of relationship.

I have seen this in my life, where near centenarians lived alongside those who died young. No algorithm could have foretold the stubborn vitality of one, or the sudden frailty of another. The Christian story interrupts the arithmetic: death is not fulfilled prediction but revealed promise. In Christ, mortality is not managed destiny but mystery.

Mortality Forecasting in End-of-Life

AI now enters with the promise of precision in end-of-life care. 1 2 Prognostic scores, decline forecasts, timed hospice referrals promise to tell us the measure of our remaining days and hours. These tools can aid planning, but they also tempt us to treat dying as a countdown—numbers replacing presence, probability replacing mystery. The danger is not only inaccuracy, but inevitability. When probability is mistaken for prophecy, patients may feel compelled to live — or die — according to the algorithm’s forecast.

For Christians, mortality is never a forecast. Our times are not held by metrics but by God, who numbers our days and promises His presence at the end of them. To die in Christ is not to reach the end but to be gathered into His promise of life beyond physical death to start eternity.

Christian Accompaniment Beyond Metrics

Against this arithmetic of AI stands the stubborn unpredictability of human relationships. Research confirms what hospice pioneers intuited: social connection is as vital as any drug. A meta-analysis 3 of 148 studies found that strong social ties improve survival odds by 50% — an effect size greater than many biomedical interventions. Social connection matters more than prediction and metrics at end-of-life.

Christian accompaniment is something more than social connection. It is not only being with the dying but being with them in seeking to embody the love of Christ. It is a presence to echo Jesus’s promise, “I am with you always, to the end of the age.” (Matthew 28:20). Such accompaniment resists the reduction of dying to metrics.

The Ars Moriendi: Why It Matters Now

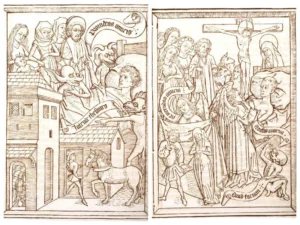

Woodcut illustrations by Weigel. The dying Christian is tempted by greed and then triumphs over the temptation, surrounded by angels.

The Ars moriendi, composed in fifteen-century Europe, offered guidance for a good death: six chapters on dying well according to Christian precepts of the late Middle Ages. Each one carries uncanny resonance in our own age of AI prediction and invokes questions for deeper reflections.

Consolation: Then, death was not to be feared but trusted as passage. Now, against AI’s countdowns, we must remember that death is not a failure but part of life’s gift.

Five temptations: Then, lack of faith, despair, impatience, pride, avarice. Now, technological temptations: despair at prognosis, impatience to schedule death, pride in mastery, reduction of care to cost; and lack of faith.

Seven questions: Then, questions opened the soul to Christ’s consolation. Do you believe? Do you repent of your sins? Do you forgive others? Do you hope in God’s mercy? Do you accept suffering patiently? Do you renounce pride and self-reliance? (humility) Do you let go of worldly attachments?

Now, do we ask only about eligibility for interventions, or dare to ask the dying about meaning, reconciliation, forgiveness, and hope?

Imitating Christ’s life: Then, Christ’s surrender was the model. Now, His death remains the measure: not calculation but gift.

Guidance for family: Then, rules for bedside presence. Now, presence is still medicine. Companionship, touch, and witness resist the reduction of dying to metrics.

Prayers for the dying: Then, words of hope and blessing. Now, what are our prayers? Al-driven algorithms – or words that carry lament, gratitude, and promise? Even in silence, prayer resists the arithmetic of prediction.

The Ars moriendi was born in the shadow of plague. Ars Moriendi 2.0 is born in the shadow of AI-powered prediction. It is uncanny that just as AI promises to script our dying into countdowns, this ancient manual re‑enters the conversation. Perhaps this timing is no accident. AI prediction prompts the renewal of the art of dying.

Christ’s death remains the measure. His surrender was not a calculation but gift that gave life to the world. Every death, however ordinary, echoes that mystery: it is never only about the one who dies, but about the life given forward.

In an age of AI-driven algorithms, the art of dying must be reclaimed as presence, as communion, as gift.

That is Ars Moriendi 2.0 – a prophetic reminder of Christ’s promise revealed.

References

- Machine learning model for prediction of palliative care phases in patients with advanced cancer: a retrospective study | BMC Palliative Care | Full Text

- An overview of the role of artificial intelligence in palliative care: a quasi-systematic review | Bork-Zalewska | Palliative Medicine in Practice

- Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review – PMC

Views and opinions expressed by authors and editors are their own and do not necessarily reflect the view of AI and Faith or any of its leadership.