Introduction

End-of-life decision making can be physically, emotionally, and spiritually excruciating. Choices made by loved ones or professional caregivers during this time directly impact the patient’s quality of life. Palliative care is the interdisciplinary medical area aimed at optimizing quality of life for those with complex terminal illnesses. Both palliative care and the related hospice movement have greatly improved end-of-life care in recent decades, but the demand continues to outpace supply worldwide. Knaul et. al. predict that between 2016 and 2060 there will be an estimated 87% global rise in the number of deaths following serious health-related suffering, with low-income countries experiencing the largest proportional increase 1. This increased demand implies that many end-of-life decisions will be made by physicians who, while highly skilled and acting in their patient’s best interest, may lack palliative expertise. Furthermore, palliative care in the United States is expensive, accounting for 13-25% of total Medicare expenditure 2 as well as further saddling patients and their families with large medical bills 3.

Given these systemic problems, AI agents have been proposed as a suitable aid. An AI trained by palliative care specialists could help non-specialists make better end-of-life decisions, while also acting as a scalable, cost-saving measure when appropriate. Furthermore, AI specializes in analysing complicated, high-dimensional, and multimodal datasets to help physicians make objective decisions. In theory, the properties of AI should make it amenable to the datasets and decision-making required in the field of palliative care. However, the potential for using AI in palliative care raises some important ethical and theological questions that Christians ought to consider.

In other areas of medicine, AI may be employed to supply insights to patients, family, and medical staff, but final decisions are made by people, not machines 4. It is possible that palliative care decisions can be augmented by AI, but AI can never replace human care, and care providers unambiguously retain the full responsibility for their decisions. How should we, as Christians, think about end-of-life decisions, and how should an AI be trained to suitably match our own palliative care goals?

End-Of-Life Treatment and Decision Augmentation

While AI is already playing an active part in medical fields like drug discovery 5, radiology 6, and electronic health records 7, these technologies do not appear to have reached the specific field of palliative care. This may be attributed to ethical concerns in conjunction with data availability. Of the handful of papers in this domain, nearly all constructed models seek to predict a patient’s mortality over a six-month or year-long time horizon 89 1011. Such a prediction is obviously important to a patient and their loved ones. This will also shape how a care provider considers the various treatments and measures ultimately aimed at optimizing a patient’s quality of life. In addition to mortality predictions, AI could also be used to incorporate a patient’s specific medical situation when balancing important trade-offs in how and when treatments are administered 12.

Many treatments considered by palliative care providers are unique to the context of palliative care because of the serious trade-offs that must be negotiated. For example, suppose a patient has terminal metastatic cancer, with metastases developing in the brain. Tumor growth in the brain will cause steady cognitive decline, leading to a decreased quality of life. Therefore, physicians may recommend whole-brain radiation therapy to kill tumor cells and delay cognitive decline. Yet, whole-brain radiation therapy is linked to cognitive decline over a longer time horizon. The treatment decision that accurately optimizes for a patient’s quality of life will be based on many factors, including how much longer the patient is expected to live.

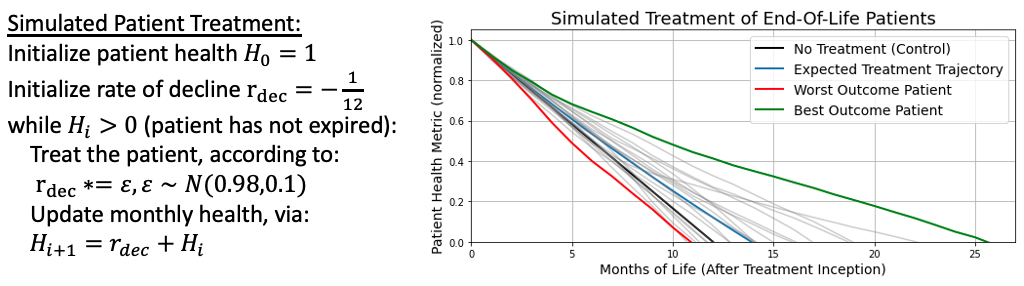

To understand how an AI might reason about such treatment decisions, let us analogize the problem within the simple mathematical framework as shown in Figure 1. Suppose we measure a patient’s initial health upon a terminal diagnosis (with respect to some indicator, such as cognitive capacity). Further, let us assume that, without intervention, a patient will decline in health at a constant rate over the course of one year, after which they expire (shown with the black line). Fortunately, a monthly treatment is available which will, on average, decelerate a patient’s rate of decline by 2%, thereby extending their life. This deceleration will, on average, lead to around two more months of life (shown with the blue line). However, varying patients will respond to the treatment differently, depending on a multitude of factors. In our simplified situation, we will account for this variation by sampling the rate of decline from a normal distribution with a set variance. Simulating twenty patients under these conditions, we find that the treatment can be a tremendous benefit to some (extending the life the best outcome patient by more than a year of life, as shown in the green line), but a burden to others (shortening the life of the worst outcome patient by about a month compared to the control, as shown in the red line).

Figure 1: A simple mathematical framework for simulated patient health decline, with and without treatment. In probability theory, this system is an example of a martingale.

To be clear, this mathematical framework omits many important factors. Treatments may be started, stopped, or restarted for a variety of reasons. Not all patients will begin a treatment at the same level of health, and their overall health will not improve or decline based on a simple formula. For a patient undergoing multiple types of treatment, the degree to which any single measure is helping or hurting a patient is not usually well understood. However, this framework does illustrate how an AI would reason through a treatment strategy: starting from a simple baseline (the known efficacy of a treatment on average), an AI can begin incorporating patient-specific medical information to suggest different courses of action which vary by individual. Just as a treatment by itself will help some and hurt others, an AI will suggest courses of action which sometimes help, and sometimes hurt. This simple framework also illustrates that even in situations stripped of nearly all complexity, making a treatment decision can be difficult. While there is no easy solution to such treatment decisions, Christians can draw from a long history of caring for those who are dying, those who are lost, and those who are enduring great pain.

Vitalism Vs. a Theology for Hospice

The common secular humanistic understanding is that those who die simply cease to exist. Such an understanding paves the way to vitalism: the belief that biological life must be preserved at all costs. For many people, including Christians, accepting the trade-offs implicit to palliative care through hospice admission can feel like giving into death. Advances in medicine and technology have convinced some that death may not be inevitable after all, like a serpent in our ear, whispering “surely you shall not die.” Admitting mortality becomes tantamount to a personal failure. An AI trained with an implicit bias towards vitalism may ultimately extend a patient’s life, but at what cost?

In a 2021 article entitled Opposing Vitalism and Embracing Hospice: How a Theology of the Sabbath Can Inform End-of-Life Care, Sarah K. Sawicki describes the dangers of vitalism and cites how it leads patients and caregivers to delay or entirely forego palliative care 13. Sawicki builds on the Jewish scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel’s distinction of the “sacredness of space,” which is our understanding of God’s charge to humanity over the material world, versus the “sacredness of time,” which is our understanding of God’s dominion over the past, present, and future 14. As such, God created the Sabbath for our benefit as a day set apart to acknowledge this sacredness of time by temporarily giving up the sacredness of space and foregoing our aims to reshape the material world. Extending a theology of Sabbath to hospice, Sawicki writes, “hospice programs can be seen as a Sabbath period for modern medicine: a time where the focus is not on striving, work, or aggressive treatments (the things of Space), but rather a special time-holy, set apart-for the specific goals and needs of terminal patients at the end of life.” This Sabbath understanding should affect how we make end-of-life decisions, and how we construct AI to aid us in our decision making.

In the fourth century, the lives of Macrina the Younger, her brother Gregory of Nyssa, and their mother demonstrated a Christian method of palliative care. As their mother died, Gregory wrote of his sister: “ both preserved herself from collapse, and becoming the prop of her mother’s weakness, raised her up from the abyss of grief, and by her own steadfastness and imperturbability taught her mother’s soul to be brave.” Gregory carefully noted that Macrina kept up her own strength while also giving herself wholly to her mother’s care. Years later, when Macrina approached her own death, she encouraged Gregory to “rest body awhile,” mindful of his needs, though she was in great pain. As she died, she prayed, “Thou, O Lord, hast freed us from the fear of death.” If we, like Macrina, believe that “the end of this life the beginning…of true life” 15, we are empowered to support patients with a Sabbath of palliative care rather than a workweek of vitalistic care. Vitalism defies the natural end of our mortal bodies, while Sabbatarian palliative care acknowledges natural rhythms of life, allowing ashes to be ashes and dust to be dust.

AI applied to palliative care, if properly designed, has the potential to help us focus on caring for those who are near death, aiding our decision-making to be guided by wisdom and love rather than fear. AI has added value in many healthcare disciplines, and is likely to tackle important subproblems in palliative care as well. But before an AI can suggest decisions that match our priorities, we must decide what our priorities should be. A Sabbatarian understanding provides Christians with these priorities, orienting us towards God even in our final season of life on Earth.

Conclusion

End-of-life decisions can be fraught with difficulty. Loved ones faced with making decisions for patients often feel confused and lacking in support. Applying AI opens opportunities for aiding patients and medical professionals to assess some palliative care decisions in an objective way. It will remain important to ensure AI does not exhibit systematic biases against protected classes, as pointed out in other areas of medicine. AI also comes with other drawbacks, such as being unable to account for external confounding factors which may be more apparent to a care professional. With these drawbacks in mind, AI is designed to optimize towards a certain objective, be it length of life, quality of life, or some combination of these, and make suggestions for care without a maelstrom of emotions clouding judgment. As Christians, palliative care and hospice are not frightening, but can be inhabited as a sacred time set apart for giving up oneself and one’s beloved to God. In death, we look towards that certain hope of the Resurrection, when “he will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Rev. 21:4, ESV). Amen.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Melody Cantwell for her advice, suggestions, edits, thoughtful questions, and the story of Gregory and Macrina. Thanks to Emily Wenger for proofreading, editing, and publishing this work.

References

Knaul, Felicia Marie, Paul E. Farmer, Eric L. Krakauer, Liliana De Lima, Afsan Bhadelia, Xiaoxiao Jiang Kwete, Héctor Arreola-Ornelas et al. “Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report.” The Lancet 391, no. 10128 (2018): 1391-1454.

Duncan, Ian, Tamim Ahmed, Henry Dove, and Terri L. Maxwell. “Medicare cost at end of life.” American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 36, no. 8 (2019): 705-710.

Joynt, Karen E., Jose F. Figueroa, Nancy Beaulieu, Robert C. Wild, E. John Orav, and Ashish K. Jha. “Segmenting high-cost Medicare patients into potentially actionable cohorts.” In Healthcare, vol. 5, no. 1-2, pp. 62-67. Elsevier, 2017.

Nyholm, Sven, and Jilles Smids. “The ethics of accident-algorithms for self-driving cars: An applied trolley problem?.” Ethical theory and moral practice 19, no. 5 (2016): 1275-1289.

Chan, HC Stephen, Hanbin Shan, Thamani Dahoun, Horst Vogel, and Shuguang Yuan. “Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence.” Trends in pharmacological sciences 40, no. 8 (2019): 592-604.

Syed, Ali B., and Adam C. Zoga. “Artificial intelligence in radiology: current technology and future directions.” In Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology, vol. 22, no. 05, pp. 540-545. Thieme medical publishers, 2018.

Juhn, Young, and Hongfang Liu. “Artificial intelligence approaches using natural language processing to advance EHR-based clinical research.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 145, no. 2 (2020): 463-469.

Storick, Virginia, Aoife O’Herlihy, Sarah Abdelhafeez, Rakesh Ahmed, and Peter May. “Improving palliative care with machine learning and routine data: a rapid review.” HRB Open Research 2 (2019).

Einav, Liran, Amy Finkelstein, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Ziad Obermeyer. “Predictive modeling of US health care spending in late life.” Science 360, no. 6396 (2018): 1462-1465.

Makar, Maggie, Marzyeh Ghassemi, David M. Cutler, and Ziad Obermeyer. “Short-term mortality prediction for elderly patients using medicare claims data.” International journal of machine learning and computing 5, no. 3 (2015): 192.

Sahni, Nishant, Gyorgy Simon, and Rashi Arora. “Development and validation of machine learning models for prediction of 1-year mortality utilizing electronic medical record data available at the end of hospitalization in multicondition patients: a proof-of-concept study.” Journal of general internal medicine 33 (2018): 921-928.

Windisch, Paul, Caroline Hertler, David Blum, Daniel Zwahlen, and Robert Förster. “Leveraging advances in artificial intelligence to improve the quality and timing of palliative care.” Cancers 12, no. 5 (2020): 1149.

Sawicki, Sarah K. “Opposing vitalism and embracing hospice: How a theology of the Sabbath can inform end-of-life care.” Christian bioethics: Non-Ecumenical Studies in Medical Morality 27, no. 2 (2021): 169-182.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. The sabbath. MacMillan, 1951.

Gregory of Nyssa, Life of Macrina, trans. W. K. Lowther Clarke. London, SPCK (1916). <https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/macrina.asp>